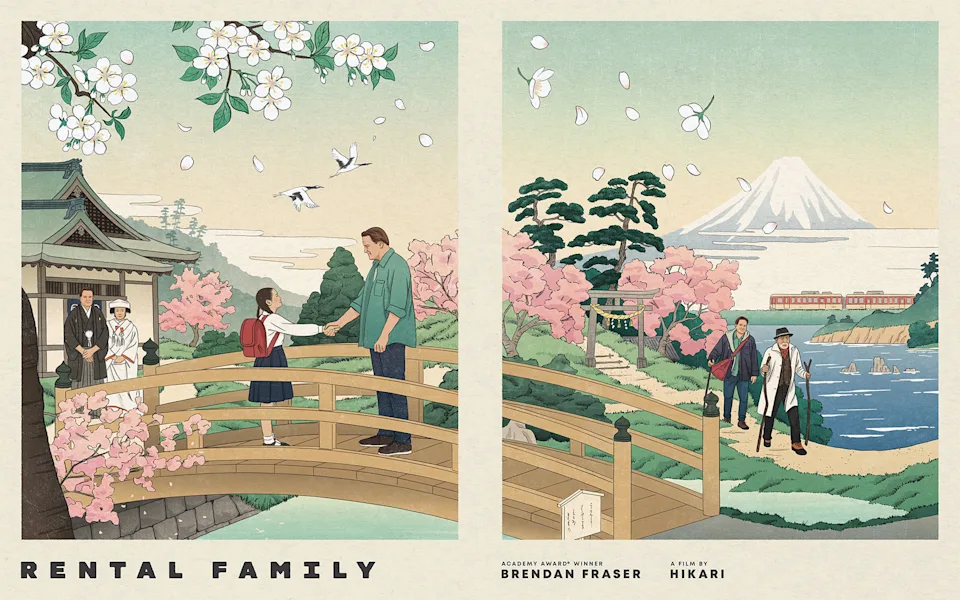

Cinema has a peculiar way of mirroring our most intimate insecurities. Some films do it through grand spectacle, others through hushed conversations in dimly lit rooms. Rental Family, directed by Hikari, belongs firmly in the latter category. Set against the sprawling, meticulously organized chaos of Tokyo, the film is a quiet meditation on performance, both as a profession and as a way of surviving in an increasingly disconnected world.

At first glance, the premise feels almost dystopian: a company that provides “rented relationships” for those who cannot, or will not form genuine ones. But what could have easily devolved into satire or melodrama instead unfolds as a deeply human, often melancholic exploration of identity, belonging, and the blurred line between reality and acting.

This is not a flashy film. It does not grab you by the collar. Instead, it seeps into your thoughts gradually, lingering long after the final frame fades.

The Unsettling Premise: Love, Loss, and Manufactured Connections

The foundation of Rental Family rests on a very real cultural phenomenon in Japan, businesses that allow people to “rent” actors to play roles in their lives. These can range from fake wedding guests to stand in parents, surrogate partners, or even professional mourners.

On paper, this sounds bizarre. Morally questionable. Even slightly disturbing.

Yet, Hikari approaches this world not with judgment but with curiosity. Rather than mocking the clients or sensationalizing the concept, the film asks a far more uncomfortable question: If real relationships fail us, is a manufactured one better than nothing?

Through the story, we meet people who turn to Rental Family not out of cruelty, but out of desperation, loneliness, shame, social pressure, or a deep longing to be seen.

The film gently suggests that while these services may be artificial, the emotions they evoke are painfully real.

Phillip Vandarploueg: A Man Trapped Between Roles

At the center of the story is Phillip Vandarploueg, portrayed with remarkable restraint by Brendan Fraser.

Phillip is an American actor who once found fleeting success in Japan as the face of a toothpaste brand an absurd yet oddly fitting metaphor for his career. He was once the “Toothpaste Man,” a grinning, larger than life mascot plastered across billboards and commercials. But fame in advertising is fickle, and now he exists in a limbo between relevance and obscurity.

He lives alone in a cramped Tokyo apartment, surrounded by remnants of his past glory most notably a cardboard standee of his toothpaste character that dominates his living space. This image is both funny and tragic: a man literally haunted by a caricature of his former self.

What struck me most about Phillip is his deep, almost oppressive solitude. The film repeatedly shows him gazing out his window at neighboring apartments where families laugh, argue, cook, and live. These quiet moments are devastating in their simplicity. He is close enough to witness life, yet perpetually excluded from it.

Fraser’s performance is subtle but powerful. His face carries a permanent expression of quiet resignation, as if he is constantly bracing himself against disappointment. He is not dramatic in his misery; he is simply weary.

Entering the World of Rental Family

Phillip’s journey into the Rental Family business begins almost accidentally.

His agent sends him to what he believes is an acting job requiring formal attire. Instead, he finds himself at a staged funeral for a man who is still very much alive. The bizarre scenario is both darkly comedic and strangely poignant. The “deceased” lies in an open casket, listening to strangers deliver heartfelt eulogies about his life.

For Phillip, this experience is deeply unsettling. At one point, he even climbs into the coffin himself, as if contemplating his own mortality or questioning whether his life has meaning.

This scene is crucial. It establishes the film’s tonal balance between discomfort, absurdity, and emotional sincerity.

Soon after, Phillip is recruited by Rental Family, a company led by Shinji, played with impressive nuance by Takehiro Hira. Shinji is pragmatic, businesslike, and emotionally guarded. To him, this work is a service, not a moral dilemma.

Phillip, however, cannot detach himself so easily.

The Invisible Cost of Running Empathy as a Business

One of the things that slowly began to trouble me as the film progressed was not just the ethics of the clients, but the quiet emotional burden carried by the people running this business. On paper, Rental Family is almost admirable. It is built around helping people filling gaps that society, relationships, or circumstances have left behind. There is a logic to it, even a kind of kindness.

And yet, the film subtly reveals something far more unsettling: while the business serves others, it offers very little emotional refuge for the people who work there.

Shinji and Aiko, in particular, move from one fabricated relationship to another, absorbing grief, anger, nostalgia, and loneliness without ever being allowed to process their own. They are constantly present for others, yet largely absent from their own lives. There is a quiet emptiness that lingers around them, not dramatic, but deeply felt.

This is where Rental Family becomes quietly heartbreaking. The film suggests that while such a business may function efficiently, it is built on an unsustainable emotional model. Humans are not machines that can simply download feelings for a job, upload them onto someone else, and then wipe their memory clean. Every interaction leaves a trace. Every role leaves a residue.

No matter how professional or detached one tries to be, emotions accumulate. Experiences stack up. Memories linger. The film gently but firmly reminds us that we cannot reset ourselves like robots or clear our emotional cache after every assignment.

In that sense, the business is both helpful and cruel, helpful to its clients, but emotionally taxing on its employees. It highlights a fundamental truth about being human: we are fragile, impressionable, and porous. We carry our past with us, whether we like it or not.

And perhaps that is the film’s quiet wisdom. In a world obsessed with efficiency, convenience, and transactional relationships, Rental Family reminds us that people are not tools to be rented, used, and returned unchanged. We are shaped by every connection we make, real or staged.

A Series of Performances That Feel Too Real

As Phillip takes on more assignments, we see a variety of clients who rely on Rental Family for different reasons:

- He plays a fake Canadian groom to help a bride save face in front of her parents.

- He acts as the “token sad American” at another staged funeral.

- He becomes the gaming buddy of a socially isolated man who has spent years glued to his console.

- His colleague Aiko (Mari Yamamoto) is often tasked with even more emotionally draining roles, frequently standing in as the mistress of married men and absorbing the anger of their betrayed wives.

Each of these scenarios is handled with care. The film avoids caricatures. Instead, it portrays these clients as flawed, vulnerable, and painfully human.

What makes Phillip different from his coworkers is how deeply he invests in every role. He doesn’t just perform; he feels. And that becomes both his strength and his undoing.

The Two Assignments That Change Everything

The narrative takes a serious turn when Phillip is given two particularly complex jobs.

- Interviewing the Forgotten Actor

Phillip is hired to pose as a journalist interviewing Kikuo, a once famous but now largely forgotten actor who is slowly losing his memory.

What begins as a simple deception gradually evolves into something far more emotionally layered. As Phillip listens to Kikuo recount fragmented stories of his past, he begins to see parallels between their lives two actors trapped in different stages of obscurity. Without spoiling too much, this storyline ventures into slightly implausible territory, but its emotional core remains compelling. It raises profound questions about legacy, memory, and what it means to be remembered.

- Playing a Father to a Lonely Girl

The second assignment is even more troubling.

A single mother hires Phillip to pretend to be the estranged father of her 11 year old daughter, Mia, in order to improve the girl’s chances of getting into an elite middle school.

Morally, this is a nightmare.

As a viewer, I felt an immediate sense of unease. Hiring a stranger to impersonate your child’s father even temporarily feels reckless and potentially damaging. It is not good parenting, no matter how noble the intention.

Yet, the film refuses to paint the mother as a villain. She is desperate, overworked, and terrified of failing her child in a hyper competitive society.

Phillip, meanwhile, finds himself unexpectedly drawn to Mia. Their interactions are tender, awkward, and heartbreakingly sincere. What starts as a role slowly begins to blur into something real.

He listens to her, supports her, and becomes the kind of father figure he never had and secretly wishes he could be. This is where the film becomes emotionally devastating. Phillip knows he cannot truly be her father, yet he cannot bring himself to fully detach either.

Performance vs. Reality: Where Does the Line Exist?

One of the film’s most fascinating themes is the idea that acting is not just a profession but a way of navigating life.

Phillip begins to interpret his role in Rental Family not as deception, but as an opportunity to provide comfort, closure, or meaning to others. In doing so, he often bends the rules sometimes to the point of risking his job or even legal trouble.

In one particularly memorable sequence, he helps an elderly client “escape” from a care facility to fulfill a long-held wish. It is both touching and ethically questionable, perfectly encapsulating the film’s moral ambiguity.

Hikari never gives easy answers. Instead, the movie invites us to sit with the discomfort and ask ourselves: Is it wrong to lie if the result brings happiness?

A Film That Feels Intimate, Not Grand

Stylistically, Rental Family is understated. The cinematography favors natural light and everyday Tokyo landscapes rather than neon lit nightlife. This gives the film a grounded, almost documentary like texture.

At times, it feels less like a traditional movie and more like an observational study of modern loneliness.

Some viewers may find this pacing slow or emotionally heavy. But for me, that restraint is what makes the film so powerful.

Brendan Fraser’s Quiet Reinvention

Watching Fraser in this role is fascinating, especially considering his career resurgence in recent years.

There is a sadness in his portrayal that feels deeply personal. Phillip is not just a struggling actor; he is a man searching for relevance, connection, and purpose.

While this emotional heaviness worked brilliantly in The Whale, it occasionally makes Rental Family feel a bit too somber. A touch more humor might have lightened the mood without undermining the film’s depth.

Still, Fraser’s performance is compelling. He embodies Phillip with sincerity, vulnerability, and quiet dignity.

What the Film Ultimately Says About Us

By the end of Rental Family, I found myself reflecting less on the company itself and more on what it represents.

We live in an era of curated identities, transactional relationships, and emotional isolation. Social media allows us to perform versions of ourselves just as Phillip performs his roles. We, too, often fake happiness, connection, or confidence.

In that sense, the film feels painfully relevant.

Rental Family may be an exaggerated concept, but the emotional void it fills is very real.

Final Thoughts

Rental Family is not a perfect film. It occasionally leans toward sentimentality, and some plot elements stretch credibility. But its emotional intelligence, nuanced performances, and philosophical depth more than compensate.

This is a film about acting, yes, but also about longing, identity, and the universal human desire to matter.

In Phillip’s journey, we see our own insecurities reflected back at us: the fear of being forgotten, the ache of loneliness, and the hope that, somewhere, someone truly sees us.

And that, more than anything, is what makes Rental Family a deeply moving and unforgettable experience.

Comments